整理自《終極股息投資攻略》第4章,作者來自美國基金評(píng)級(jí)公司晨星(Morningstar)。

A Tale of Two Seat Makers (1)Before taking the helm at Morningstar Dividendlnvestor, I was an analyst covering the auto and auto parts industries. These are not companies known for stable or attractive income; the Big Three (well, they used to be big) had a habit of paying out huge dividends in boom years and slicing them quickly when car sales turned sour. Ford (F) is in so much trouble these days that it isn't paying a dividend at all. Even though several parts suppliers are in better shape than their customers, good yields are hard to come by.

Yet two companies from the auto parts industry provide two of my favorite examples of the role of dividends in business and shareholder results: one that is very good, and one that is pretty bad.One of the great growth stories of the automotive industry in the 1990s came in, of all places, the driver's seat--and all other seats as well. General Motors, Ford, and the other domestic manufacturers were starting to move the assembly of seats out of their car factories to supplier shops, where the work could be done more efficiently (and at a much lower cost of labor). Two companies dominated this emerging industry from day one: Lear (LEA) and Johnson Controls (JCI). Lear had been carved out of a larger conglomerate through a leveraged buyout and was saddled with heavy debt. Johnson Controls, by contrast, was already a 100-year-old company by that point; its founder had invented the thermostat in 1883. It entered the automotive seating business by acquiring Hoover Universal in 1985.

Both businesses grew rapidly, but when Lear came public in 1994, it might have looked like the better of the two. It was focused strictly on automotive parts, while Johnson Controls had other businesses (batteries, building controls, even plastic soda bottles). What Johnson Controls had back then, and Lear did not, was a dividend.

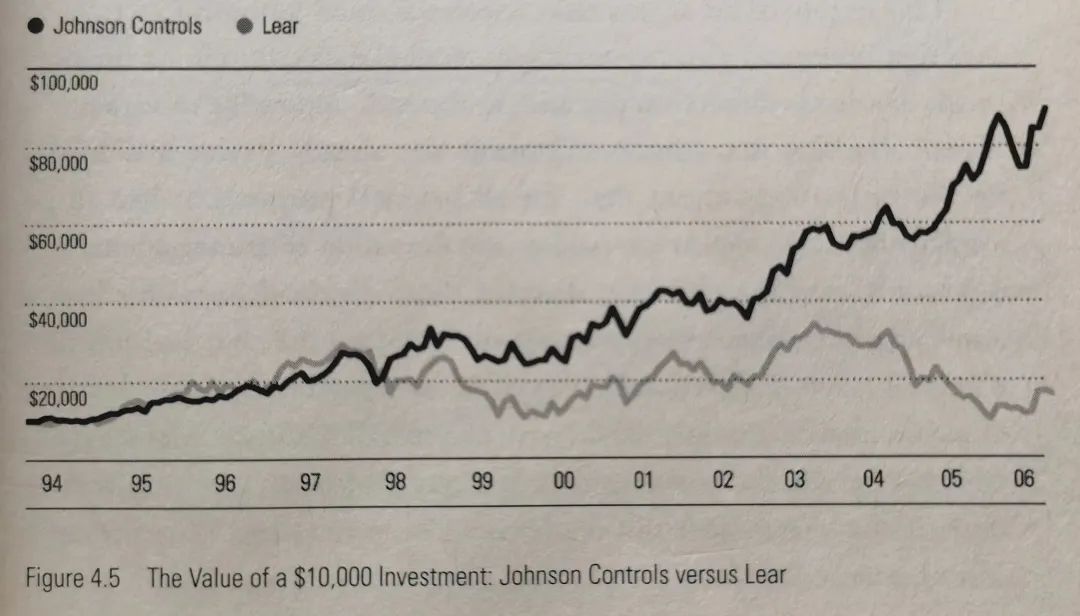

Despite comparable growth potential and profitability, a $10,000 investment in Lear in April 1995 was worth only $16,117 a decade later. That represents an annualized total return of just 3.9 percent, less than half of what an S&P 500 Index fund would have earned; heck, that's less than a money market fund! The same investment in Johnson Controls, with dividends reinvested, grew to $89,153: an annualized total return of 18.9 percent. (See Figure 4.5.)

What accounts for this gaping difference? Numerous factors can be considered. For one, Johnson Controls had a more attractive roster of customers from the start. Its earliest customer, Toyota (TM), was already on its way to quadrupling its share of the North American vehicle market, and it did significant business with Nissan (NSANY) and Honda (HMC), too. Lear captured a greater share of the business from Detroit--GM, Ford, and Chrysler--only to watch those manufacturers drop from 80 percent of the market to little more than 50 percent. That's a huge factor, one that an analyst certainly wouldn't want to shortchange. Also, Johnson Controls owned some other businesses that included its traditional building climate control unit as well as the country's largest manufacturer of automotive batteries. Lear only made auto parts.

In my view, the important factor explaining the different outcomes for each firm is visible in their capitalallocation practices. In the mid- and late 1990s, Lear spent billions of dollars, almost always provided by junk bonds and other high-yield debt, to purchase just about any auto parts supplier that made interior components. Johnson Controls made some big acquisitions too, but its deals were generally smaller and quickly paid for through operating cash flow.One other point: In its first nine years as a public company, Lear never paid a dividend. Johnson Controls paid a dividend in every quarter over this stretch, lengthening a streak of continuous dividend payments going back to 1887--a fact that the press releases announcing the firm's dividends never fails to mention.

Lear didn't pay even a penny's worth of dividends until 2003, and even that change of stripes couldn't survive the auto industry's ongoing bath. Unable to generate enough cash flow in early 2006 to meet its debt obligations and pay for a costly restructuring of its business, Lear eliminated its dividend. Shareholders received only 10 quarterly payments totaling $2.25 a share before the dividend rate returned to zero. Meanwhile, Johnson Controls went on raising its dividend; in early 2007, it paid dividends at an annual rate equal to 11 percent of its share price in April 1994.