繼續(xù)整理學習美國投資書《終極股息投資攻略》第5章�����,作者來自美國基金評級公司晨星(Morningstar)�����。

Dividend Payout Ratios

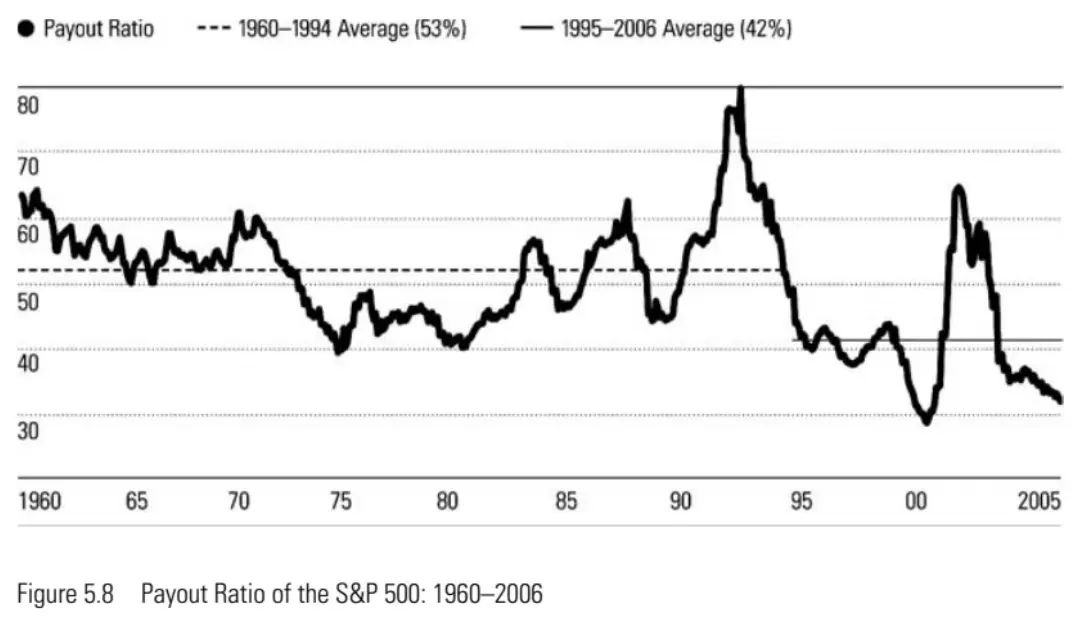

Using dividends to evaluate the prospects for individual stocks, and for the market as a whole, is a minority discipline. Most of the wags on Wall Street are looking at earnings per share, not dividends. Since 1960, earnings per share for the S&P 500 have grown at 7.3 percent annually, ahead of the 5.8 percent growth rate for dividends, but an almost perfect match with the S&P's 7.2 percent average pace of price appreciation. But if profit growth exceeds dividend increases, that means payout ratios are falling--and indeed they have, to record lows. (See Figure 5.8.)

As with the S&P's dividend yield, payout ratios appear to have experienced two distinct eras. Between 1960 and 1994, companies paid out an average of 53 percent of their earnings. Since then, the average has run at 42 percent. At the end of 2006, this figure was only 32 percent.

Leaving all other considerations aside for a moment, today's low payout ratios certainly suggest that American corporations could afford to be a bit more generous with their dividend payments. If the S&P's 500 member firms increased their collective payout ratio from 32 percent to the old average of 53 percent, dividends per S&P share would rise by nearly two thirds, which in turn would improve the yield of the index from 1.8 percent to nearly 3 percent.

Furthermore, corporate America is less capital-intensive than it used to be. In the 1950s or 1960s, economic growth meant building more steel mills, car factories, and oil refineries. If firms like these turned a $10 million profit, but then had to reinvest $7 million to acquire more of these costly kinds of assets, only $3 million was left for shareholder dividends. Today, however, economic growth is much more likely to be knowledge-based: scientific research, new product development, marketing, and the like. These investments don't create assets in the balance-sheet sense of the word, so whatever a business spends on these activities is deducted from current profits. This in turn means that the earnings that the shareholder sees are much closer to what she actually stands to benefit from. So returns on equity--especially if we exclude the accounting entries necessitated by acquisitions--are noticeably higher than they once were.

In the meantime, it's fair to ask where all these retained earnings are going--the 68 percent of profits that aren't being fed back into shareholders' pockets via dividends. Regrettably, the bulk of these funds aren't being reinvested in core business activities that generate high returns on equity. Most are going toward share buybacks. While not tantamount to dividends--they don't put dollars in your brokerage account unless you choose to sell--these buybacks still stand to improve future rates of dividend growth.

So for now, let's count today's low payout ratio as providing an extra percentage point or so of future dividend growth potential, with perhaps still another percentage point traceable to the changing nature of economic growth. But the final question is the toughest: Can current levels of profitability persist?